Imagine you’re six years old, living in a small town in Southern California, where you and your brothers and sisters have always lived and gone to school. One morning, your parents, who also grew up

Imagine you’re six years old, living in a small town in Southern California, where you and your brothers and sisters have always lived and gone to school. One morning, your parents, who also grew up  in the same town and own a hardware store, tell you that by the end of the next day the family must take everything they can carry, board a train, and move to a camp in a place called Wyoming; a place with barbed-wire fences, armed guards, and cramped living quarters. Why? Because even though you and your family are American Citizens, you’re Japanese and the United States is at War with Japan.

in the same town and own a hardware store, tell you that by the end of the next day the family must take everything they can carry, board a train, and move to a camp in a place called Wyoming; a place with barbed-wire fences, armed guards, and cramped living quarters. Why? Because even though you and your family are American Citizens, you’re Japanese and the United States is at War with Japan. For over 120,000 people of Japanese descent, two-thirds of which were American Citizens, this was their story in the

spring of 1942. An unfounded fear of sabotage and spying by people of Japanese descent prompted President Roosevelt to sign an executive order relocating all Japanese to camps in the interior of the US, usually in remote areas. We visited one of these locations near Cody, the Heart Mountain Relocation Center.

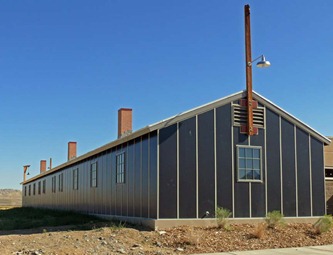

spring of 1942. An unfounded fear of sabotage and spying by people of Japanese descent prompted President Roosevelt to sign an executive order relocating all Japanese to camps in the interior of the US, usually in remote areas. We visited one of these locations near Cody, the Heart Mountain Relocation Center.  The site has a beautiful new visitor center built to resemble the original barracks and there are interpretive signs along paths throughout the former grounds of the camp. The visitor center exhibits are striking – full size pictures of internees are interspersed with camp pictures, documents, and descriptions of daily life in the camps. The camps became home for the Japanese-Americans for over three years. Gardens and fields were planted, schools were formed, small businesses were created, and even Boy and Girl Scout troops were formed.

The site has a beautiful new visitor center built to resemble the original barracks and there are interpretive signs along paths throughout the former grounds of the camp. The visitor center exhibits are striking – full size pictures of internees are interspersed with camp pictures, documents, and descriptions of daily life in the camps. The camps became home for the Japanese-Americans for over three years. Gardens and fields were planted, schools were formed, small businesses were created, and even Boy and Girl Scout troops were formed.  But it was the pictures of the children that touched us. How could the parents explain why they were here, and how could the children understand the barbed wire and the armed guards? Amazingly, the videos of the children, now elderly, all spoke of how they accepted their lives, went to school, played, and lived their lives just as other children.

But it was the pictures of the children that touched us. How could the parents explain why they were here, and how could the children understand the barbed wire and the armed guards? Amazingly, the videos of the children, now elderly, all spoke of how they accepted their lives, went to school, played, and lived their lives just as other children.  Many of the young men in the camps went on to fight honorably in the WWII European theater, but after the war, they, along with those in the camps, were unable to return to their homes due to the post-war hatred. In the end, most of the Japanese-Americans relocated throughout the country, and stoically got on with their lives without looking back. Brenda and I can understand the hysteria and fear in the early days of WWII; but it’s still hard to understand how all of the members of an ethnic group can be blamed for actions of those in another country, and we like to think that something like this could never happen now. But then again, on the wall of the last exhibit were cards that visitors had left with their thoughts. One said, “Last night at a local restaurant I overheard another patron loudly tell his friend that they should round up all of the Muslims and put them in camps”.

Many of the young men in the camps went on to fight honorably in the WWII European theater, but after the war, they, along with those in the camps, were unable to return to their homes due to the post-war hatred. In the end, most of the Japanese-Americans relocated throughout the country, and stoically got on with their lives without looking back. Brenda and I can understand the hysteria and fear in the early days of WWII; but it’s still hard to understand how all of the members of an ethnic group can be blamed for actions of those in another country, and we like to think that something like this could never happen now. But then again, on the wall of the last exhibit were cards that visitors had left with their thoughts. One said, “Last night at a local restaurant I overheard another patron loudly tell his friend that they should round up all of the Muslims and put them in camps”. In reviewing the historical information at Heart Mountain, I came across this statement that we all need to remember:

“You may think that the Constitution is your security—it is nothing but a piece of paper. You may think that the statutes are your security—they are nothing but words in a book. You may think that elaborate mechanism of government is your security—it is nothing at all, unless you have sound and uncorrupted public opinion to give life to your Constitution, to give vitality to your statutes, to make efficient your government machinery.”

—Charles Evan Hughes

Chief Justice U.S. Supreme Court, 1930-1941