Leaving Sheridan, we crossed into Montana to spend a week in the beautiful Madison Valley and the town of Ennis. A small town with lots of character, Ennis is the staging point for fly

Leaving Sheridan, we crossed into Montana to spend a week in the beautiful Madison Valley and the town of Ennis. A small town with lots of character, Ennis is the staging point for fly fisherman trying their luck on the Madison River. The town caters to fly fisherman, with many fly shops and outfitter/guides. There are some very good restaurants, especially for lunch, and some of the stores have interesting facades.

fisherman trying their luck on the Madison River. The town caters to fly fisherman, with many fly shops and outfitter/guides. There are some very good restaurants, especially for lunch, and some of the stores have interesting facades. Ennis is about 70 miles from West Yellowstone, so on a sunny day we made the trip, past amazing Earthquake Lake, Lake Hebgen Lake, and finally into West Yellowstone. I always have mixed feelings when visiting Yellowstone. It’s a beautiful place with amazing geysers, scenery, and wildlife, but it also seems to be a magnet for the most ill-mannered, inconsiderate, and downright stupid tourists we’re ever seen. Forget all of the signs that state “do not stop in the roadway” – one Bison grazing in the distance will result in a gridlock as cars come to a screeching halt and people, tablet and cell phone cameras held high in the air, run across the road to get a picture. And even on this late Spring day in May, the crowds were everywhere. Want to see Old Faithful?

Drive around for half an hour to find a parking space, then get in the long line to trek down to the geyser. And this is before school is out. We managed to get off the busy road by taking the Firehole Canyon road where the river is roaring through the canyon. Back on the main road, we watched these two large Bison. The one on the left seems to be stoically looking at the one on the right as he rolls around on the green grass.

Drive around for half an hour to find a parking space, then get in the long line to trek down to the geyser. And this is before school is out. We managed to get off the busy road by taking the Firehole Canyon road where the river is roaring through the canyon. Back on the main road, we watched these two large Bison. The one on the left seems to be stoically looking at the one on the right as he rolls around on the green grass.

Outside the park and back near Ennis, driving around the Madison Valley is an experience – in every direction are green meadows and in the distance, snow-covered mountains. We saw Moose, Bald Eagles, and Pronghorn, like these comfortably bedded down in a field of alfalfa.

One beautiful afternoon we visited Virginia City, a semi-restored mining town in

the mountains. Unlike the city in Nevada with the same name, Montana’s Virginia City has many original stores and shops with the original goods displayed, lending credence to their claims to be one of the largest American artifact sites.

the mountains. Unlike the city in Nevada with the same name, Montana’s Virginia City has many original stores and shops with the original goods displayed, lending credence to their claims to be one of the largest American artifact sites.  You can step inside and gaze at the groceries, medicines, and clothing of the 1860s. Just as interesting to us was to examine the construction of these buildings. The patchwork of boards, shingles, and metal scrap somehow worked well enough to keep these building intact for over 150 years of harsh high-desert weather.

You can step inside and gaze at the groceries, medicines, and clothing of the 1860s. Just as interesting to us was to examine the construction of these buildings. The patchwork of boards, shingles, and metal scrap somehow worked well enough to keep these building intact for over 150 years of harsh high-desert weather.

Looking at Virginia City today, it’s hard to believe that it once had a population of 5000 people in 1200 buildings, and that from the city to a point 14 miles down Alder Gulch there were 10,000 inhabitants. But no wonder, the gold strike here was the richest in the Rocky Mountains, with over 30 million dollars worth. Like most mining towns, Virginia City had it’s share of crime and when law enforcement wasn’t an answer, vigilante groups were formed.

Looking at Virginia City today, it’s hard to believe that it once had a population of 5000 people in 1200 buildings, and that from the city to a point 14 miles down Alder Gulch there were 10,000 inhabitants. But no wonder, the gold strike here was the richest in the Rocky Mountains, with over 30 million dollars worth. Like most mining towns, Virginia City had it’s share of crime and when law enforcement wasn’t an answer, vigilante groups were formed.

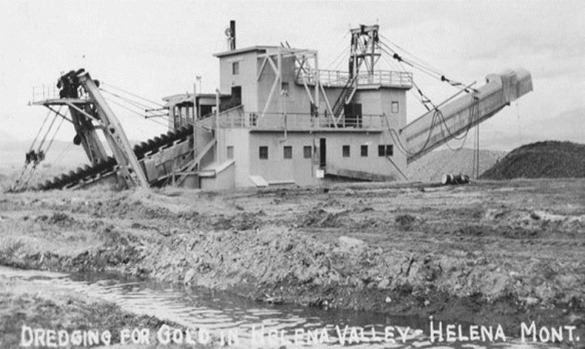

When looking at the base of Alder gulch and the town of Alder on Google Earth, I was perplexed by the strange formations - rows of something…bushes, hay? It turns out that the formations are rows of river rocks left by massive dredges that worked the small river during the early 1900s.

Four huge dredges, similar to the one pictured below were built, powered by high

voltage, and operated until the 1930s. While the gold mining stopped, the total of gold taken here in today’s prices would be two and a half billion dollars!

voltage, and operated until the 1930s. While the gold mining stopped, the total of gold taken here in today’s prices would be two and a half billion dollars!  Another interesting ghost town, and probably the most authentic you’ll see, is Bannack, located about 25 miles west of Dillon, Montana. Gold was discovered here in 1862, just a few years before Virginia City, and the town grew overnight to

Another interesting ghost town, and probably the most authentic you’ll see, is Bannack, located about 25 miles west of Dillon, Montana. Gold was discovered here in 1862, just a few years before Virginia City, and the town grew overnight to  be Montana’s largest and its territorial capital for a brief period. Remote and isolated by only one road, when the gold disappeared the town quickly lost population to Virginia City, which became the next territorial capital.

be Montana’s largest and its territorial capital for a brief period. Remote and isolated by only one road, when the gold disappeared the town quickly lost population to Virginia City, which became the next territorial capital.  Crime in both towns and the road in between was rampant, and the Montana Vigilantes ended up hanging Bannack’s allegedly corrupt sheriff and two of his deputies. The population dwindled as the mining decreased and by the 1930s there were few residents.

Crime in both towns and the road in between was rampant, and the Montana Vigilantes ended up hanging Bannack’s allegedly corrupt sheriff and two of his deputies. The population dwindled as the mining decreased and by the 1930s there were few residents.  Fortunately, the remoteness of the town helped keep it intact, and in 1954 the Montana Parks department took it over and it became a state park. They’ve done a masterful job in maintaining the park, even replacing the original “wavy” glass windows when broken by storms. You can enter and look around most of the buildings, and the interpretive center provides a movie and a good walking guide.

Fortunately, the remoteness of the town helped keep it intact, and in 1954 the Montana Parks department took it over and it became a state park. They’ve done a masterful job in maintaining the park, even replacing the original “wavy” glass windows when broken by storms. You can enter and look around most of the buildings, and the interpretive center provides a movie and a good walking guide.  During our visit we watched as scenes from a movie were being filmed, which added to the feeling that we had gone back in time. Besides the town, Bannack State park has a campground, group camping area, and picnic areas. We stopped at the town cemetery located just outside of town and walked through the old gravesites. So many of the headstones marked the deaths of children – it was a harsh life here in the 1860s.

During our visit we watched as scenes from a movie were being filmed, which added to the feeling that we had gone back in time. Besides the town, Bannack State park has a campground, group camping area, and picnic areas. We stopped at the town cemetery located just outside of town and walked through the old gravesites. So many of the headstones marked the deaths of children – it was a harsh life here in the 1860s.

We’re still traveling through Montana, so it won’t be long before another update – c’mon back!